Performances

DSO premieres compelling Violin Concerto alongside Russian favorites

Guest conductor Tabitha Berglund, violin soloist Melissa White and the Dallas […]

HGO’s “Silent Night” evokes affecting tale of WWI Christmas armistice

Christmas is a month behind us, but Houston Grand Opera summoned […]

Gardner leads the Dallas Symphony in vibrant English-Scottish program

Guest conductor Edward Gardner led the Dallas Symphony Orchestra in a […]

Luisi, Dallas Symphony bring grandeur and grit to Bruckner’s swan song

The Meyerson Symphony Center resounded Thursday night with the strains of Bruckner’s Ninth […]

Dallas Symphony takes flight with a brilliant “Butterfly”

Fabio Luisi led the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in a […]

Articles

Critic’s Choice

Music of Haydn and Mahler. Dallas Symphony Orchestra/Fabio Luisi. October 2-5 […]

Critic’s Choice for 2024-25

Tate: Woodland Songs. Dover Quartet. Sept. 17 in Houston, Oct. 19 in […]

Opera review

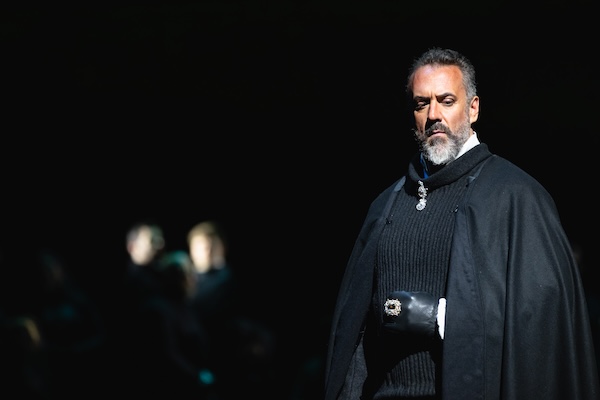

Dallas Opera present a vocally strong, visually dark “Don Carlo”

“Dark” describes the Dallas Opera’s presentation of Verdi’s Don Carlo on Friday both dramatically and literally. Director Louis Désiré’s debut production for the Dallas Opera deemphasizes the opera’s love triangle, instead exploring the effects of the underlying religious conflict and struggle for authority between the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church set against the specter of the Inquisition.

The stage was completely enveloped at the rear and at either side by three smooth gray panels having the appearance of brutalist edifices; movable platforms in the stage proper were arranged in the pattern of a broken cross.

The costumes were similarly austere, fashioned almost entirely in black, with women wearing long dresses and veils similar to sixteenth century styles, while the men’s attire resembled Spanish fashions of the late nineteenth century. Lighting consisted primarily of strong spotlights on individual characters, highlighting them on the otherwise darkened stage, and images projected onto the edifies.

Verdi’s musical setting almost invites such an approach with its comparative lack of tuneful moments and its abundance of charged interactions between the characters.

All of the principals excelled as they took up Désiré’s vision of the drama.

Christian Van Horn’s portrayal of Philip II was particularly effective; the imperiousness of his rich bass tones marked Philip II as a formidable figure even when sparring with Morris Robinson’s Grand Inquisitor in Act III, but also one capable of quiet despair as heard in his lament over the loss of Elizabeth’s love.

Robinson matched Van Horn’s imperiousness with his own resonant basso, infusing the Inquisitor’s admonitions with a degree of menace that clearly gave the king pause.

Stephen Costello’s pure and vibrant tenor instilled a hint of optimism into Don Carlo that, while dashed by the end of the opera, nonetheless seemed to energize the main character in spite of the bleak scenario.

Similarly, Etienne Dupuis, in his Dallas Opera debut, reinforced the noble selflessness of Rodrigo through his full-bodied baritone. Costello and Dupuis each displayed a liveliness that buoyed all of their individual solo and ensemble passages, but that vigor was most powerful in their duets, which strongly reinforced the friends’ camaraderie.

Nicole Car’s portrayal of Elizabeth de Valois showed the queen as suffering the most acutely in Désiré’s staging. Her clear, ringing soprano register brought a heightened urgency to Elizabeth’s confession of conflicted love to Don Carlo, her trepidation at Philip’s accusations of infidelity, and indignation upon learning of Eboli’s betrayal.

Clémentine Margaine brought a distinct intensity to the role of Eboli, using her powerful mezzo-soprano to convey the princess’s jealous fury with Carlo and to express Eboli’s remorse at implicating Elizabeth in an adulterous affair.

Bass Raymond Aceto’s exhortations as the Friar during the opening and closing moments of the opera strongly invoked the ascetic religious atmosphere at the center, while Meghan Kasanders provided the celestial soprano voice that offered faint hope to the heretics in Act II. Gretchen Krupp and David Bogaev rounded out the cast of principals respectively as Tebaldo, Elizabeth’s page, and Count Lerma/Herald.

Members of the Dallas Opera Chorus supplemented the principals throughout the performance, serving as friars in the cloister in Acts I and IV, ladies in waiting in Act II, and townspeople eager to see the punishment of heretics in Act III.

Throughout the performance, conductor Emmanuel Villaume deftly matched the pacing of the activity on stage and maintained a perfect dynamic balance among the performing forces.

Don Carlo runs through Saturday, March 7. dallasopera.org

Calendar

February 28

Chamber Music Society Fort Worth

Leonkoro String Quartet

Bosmans: […]

News

Aristo Sham takes the Gold at Cliburn Competition

In a concluding ceremony Saturday evening, Aristo Sham, 29, of Hong Kong, […]

Texas Classical Review wants you!

Texas Classical Review is looking for concert reviewers in the Dallas-Fort […]