Dove’s “Euridice” proves strange and compelling with Ars Lyrica

Douglas Williams labels himself as a bass-baritone, and the first half of that hybrid often comes to the fore in his singing, thanks to his voice’s darkness, depth and luster. Saturday night in Zilkha Hall, those sepulchral tones laid the foundation for one of Houston’s most riveting operatic portrayals in recent years.

Yet Williams performed not with an opera company, but with the Ars Lyrica baroque ensemble—and not in a baroque opera, but a 21st-century work.

That work was The Other Euridice by Jonathan Dove, a British composer best known for his opera Flight. The piece belongs to a burgeoning repertoire of new music that incorporates old instruments. Its main instrumental ensemble comprises baroque-style strings, theorbo and harpsichord; a modern soprano saxophone and oboe, playing offstage, join in at a pivotal moment.

Inspired by an Italo Calvino essay, Dove’s one-act opera stands apart from all other musical settings of the Orpheus and Euridice myth: It comes from the vantage point of Pluto, god of the underworld, The Other Euridice’s only character.

For the entire half-hour, Pluto addresses himself directly to the audience—“people of the outside,” as he calls us occupants of the earth’s surface. Not only is he distraught that Euridice was, from his viewpoint, stolen from him, but he thinks we surface-dwellers have the wrong idea of our planet.

Pluto sees his subterranean domain as the real world, and he begins by savoring the glories of its caverns, glittering minerals and blazing veins of lava. He and Euridice dreamed of having dominion over these “thriving Plutonic citadels,” he tells us, then he recounts his version of what took her away: An eruption of subterranean forces drove the two of them up through an inactive volcano to the earth’s surface, where Orpheus’ song—incarnated here by the offstage saxophone—lured her away. As the opera ends, his longing for her remains undimmed.

Dove’s music harkens back to Claudio Monteverdi by emerging in a free, almost conversational flow, Dove is that all-too-rare composer who can bring the ebb and flow of emotions to life in this way.

Pluto’s vocal line can be as natural and unforced as speech, but it crackles with excitement as describes his domain, soars as he imagines those “Plutonic citadels” and falls to earth as despair over Euridice’s absence seizes him. Rather than using melodies to express flights of emotion, Dove turns to two potent devices: Pluto periodically invokes Euridice’s name almost like an incantation, in tones ranging from resigned to passionate; and Pluto’s heartache boils over into long, wailing melismas on the vowel O.

Meanwhile, the instrumental ensemble plays a supporting role, supplying scene-setting mists of sound, punctuating Pluto’s narrative and supplying a throb of energy when as the story’s intensity builds. After the offstage saxophone spins out Orpheus’ vaulting song, the offstage oboe represents Euridice’s voice intertwining with Orpheus’.

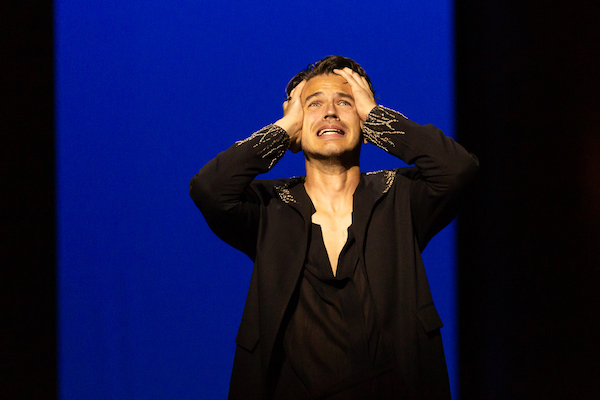

If Dove’s Pluto sounds like a man possessed, so did Williams on Saturday. The blackness of his voice’s middle and lower ranges helped conjure up Pluto’s domain—and emotional state—practically as soon as he opened his mouth, and it remained the bedrock of his portrayal.

But Williams brought the music’s every turn to life, thanks to his voice’s colors as well as his nearly infallible English enunciation.

Pluto’s words at times dripped with scorn as he described the wrongs he had suffered. When Pluto invoked his majestic domain or gave into the groundswell of his feelings, Williams’ voice resounded in Zilkha Hall—then faded into a bloodless shadow of itself when Pluto’s despair took over.

Williams’ stage presence was just as compelling, whether Pluto was spreading his arms to encompass his domain, gazing out wide-eyed as he recalled terrible sights or crumpling to the stage in heartbreak.

There was no set, but video projections conjured up lava flows and other vistas. Director Tara Faircloth’s staging moved Pluto around the space effectively.

Ars Lyrica’s ensemble, conductor by Matthew Dirst, played with a clarity, incisiveness and impact that belied its compact size.

When Pluto, late in Dove’s opera, described seeing Euridice amid a modern city, Faircloth had a gowned woman bring a chair decked with white flowers onto the stage, observed by Pluto. The woman, evidently Euridice, soon left, but that turned out to be a setup for J.S. Bach’s Cantata No. 82, Ich habe genug—which Dirst and company launched into immediately after Dove’s last chord.

The cantata is typically the property of basses, but Ars Lyrica opted instead for a mezzo-soprano, Sarah Neal. Faircloth’s staging didn’t bring her onstage first, though. Instead, baroque oboist Kathryn Montoya stepped onstage from the audience’s right—the same side from which the oboe representing Euridice in Dove’s opera had sounded. Another musician had played that, but Montoya was obviously taking up the musical mantle of Euridice. She remained onstage after Neal, the gowned woman from before, entered and began to sing.

Neal brought Bach a warm but small voice. During the first part of the opening aria, Montoya’s oboe all but drowned her out.

As Neal settled in, she treated the music to graceful, fluent turns. But the cantata’s central aria, the lullaby-like “Schlummert ein,” again pointed up her limited heft. During its low stretches, Neal again was inaudible or nearly so. In the joyful last aria, Neal sang some of Bach’s filigree adroitly, but some of it blurred. The ensemble played lightly and nimbly throughout the cantata, though, and Montoya lent a fitting mellowness to “Schlummert ein,” where she switched to an oboe da caccia.

Given that the staging had turned Neal into Euridice, one might ask: How does a figure from Greek mythology fit into a Lutheran cantata that invokes Jesus and the heavenly afterlife?

The staging evidently just ignored the Christianity. During the opening aria, where the text discusses embracing Jesus, Neal clasped oboist Montoya, who only then took her place with the rest of the instrumentalists.

But the last aria settled it. What caused the joy? As the aria began, Williams’ Pluto stepped onstage to reunite with Euridice. Yes, that’s right: The two embraced, and as the cantata ended, flower petals rained down on the happy pair. It made a decidedly bizarre ending for an evening that began with such dramatic power.

Ars Lyrica will perform 17th– and 18th-century music from the New World and Latin America on Dec. 17 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. arslyricahouston.org