A “Phoenix” to rise at HGO with world premiere of Da Ponte opera

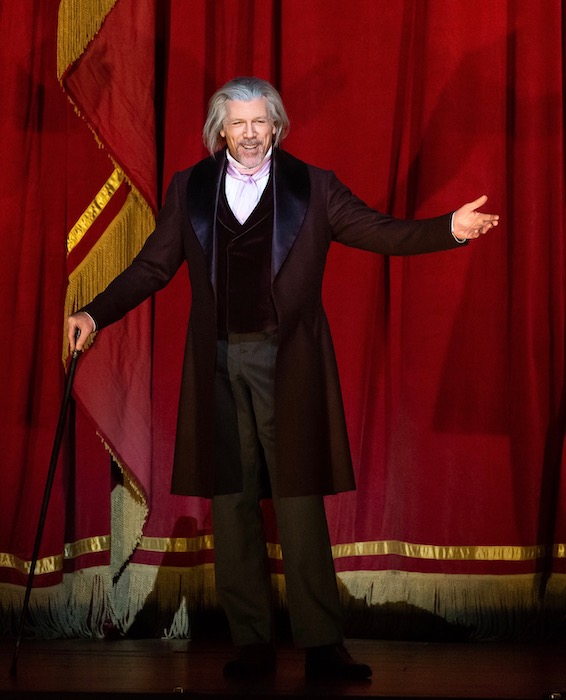

Thomas Hampson portrays the elderly Lorenzo Da Ponte in Tarik O’Regan’s “The Phoenix,” which will have its world premiere at Houston Grand Opera Friday night. Photo: Lynn Lane

In 1805, Lorenzo Da Ponte, formerly a celebrated librettist employed by the Viennese court, found himself at the lowest ebb of his life—selling groceries in rural Pennsylvania. He happened upon a review for a London performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, for which he had written the story. While gushing about the work and its performance, the reviewer failed to mention Da Ponte’s name.

“Just imagine how absolutely devastating that must have been for him to have lived an extraordinarily creative life and then been completely forgotten,” said John Caird—himself a librettist for a new opera about Da Ponte’s life.

The scene is a pivotal moment in The Phoenix, a new opera by composer Tarik O’Regan and Caird for Houston Grand Opera that will have its world premiere Friday night. The opera will explore the myriad twists and turns of Da Ponte’s rambunctious life and experiences as teacher, lover, grocer, and, most of all, writer.

“I’m always attracted to these kind of underdog characters,” says composer O’Regan. “And here is a name that is definitely not as well known as Mozart’s, considering the work they did together.”

The Phoenix splits Da Ponte’s character into two roles: an older, world-weary Da Ponte, to be sung by baritone Thomas Hampson, who muses upon his rich past life; and a younger, hard-living Da Ponte, portrayed by baritone Luca Pisaroni (Hampson’s son-in-law).

The principal conceit of The Phoenix involves Da Ponte and his son writing an opera based upon the writer’s life. Audiences will see the events of this opera-within-an-opera play out as a series of flashbacks.

“In my role, we really see him in the end of his life,” said Thomas Hampson. “He is 83 years old, he’s tired, [and] he’s slightly depressed because he feels the gods have let him down.” Da Ponte doubts his own reason to live, but finds new purpose in a new opera—called The Phoenix—which serves as a metaphor for his own misfortunes and successes, says Hampson.

“I find that [Da Ponte] has this endless energy and desire of discovering something new,” Luca Pisaroni added. “[He wanted] to be remembered and become famous like Metastasio. He never settled for something easier; he was always challenging himself, even when he was unknown.”

The title for The Phoenix comes from a letter Mozart wrote in 1782, where he praised the insight and poetic powers of a good librettist, whom he calls “that true phoenix.” Though he doesn’t mention Da Ponte by name in that specific epistle, Mozart was impressed with the high quality of the Italian writer’s work. Of course, he would eventually collaborate with Da Ponte in his three most celebrated operas, The Marriage of Figaro, Cosí fan tutte, and Don Giovanni.

Save for those major success with Mozart, Da Ponte’s life was one marked by struggle and scandal, as related in O’Regan’s opera.

He was born Emanuele Conegliano to Jewish parents in the Republic of Venice in 1749. In 1764, his father, then a widower, converted the family to Roman Catholicism in order to marry a Christian girl. The 14-year-old Emanuele adopted his new name from Monsignor Da Ponte of Ceneda, who baptized him.

Though he took minor holy orders in 1770, Lorenzo Da Ponte spend his early years as a writer of Italian and Latin poetry, even becoming a teacher of literature and languages in Venice.

But he was run out of the city in 1779, supposedly for having sired illegitimate children and his carrying on relationships with numerous women. John Caird believes that Da Ponte was actually exiled for political reasons, the writer having spoken in favor of the American Revolution, which was seen as seditious.

“He was a man who believed in freedom, he hated monarchy and the tyrannies of Europe,” Caird said. “He hated being regarded as a second-class citizen, partly because he suffered from anti-Semitism, and also because artists were regarded as the underclass at that time.”

Today, Da Ponte is most remembered for his work in the court of Vienna, where he wrote librettos for operas by Mozart, Salieri, and others. But after Emperor Joseph II died in 1790, Da Ponte lost his patron, and he ventured to France and London, where he settled for a time as an Italian language teacher and grocer. In 1805, Lorenzo, his new wife Nancy, and their children moved to the United States to escape debt and bankruptcy.=

Life in America began modestly. He sold groceries in Sunbury, Pennsylvania and he eventually opened a bookstore in New York City. Through friendships he attained an unpaid professorship teaching Italian literature at Columbia University, and eventually made his way back into theater, putting on the first American performance of Don Giovanni in New York in 1825.

Da Ponte became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1829 at age 79. Before his death in 1838, he founded and kept alive the fledgling New York City Opera Company.

In crafting the libretto for The Phoenix—complete with affairs, excitements, and all—Caird drew upon biographies about Da Ponte by Anthony Holden and Rodney Bolt. He even read all five volumes of Da Ponte’s memoirs to get a sense of his complicated past.

“Of course the more you read of Da Ponte the more you suspect that he’s either not telling the whole truth, or rationalizing his mistakes and his sins in a very self-serving way,” Caird said. “And you start getting a terrific admiration for him in one sense, but there’s also a distrust of believing his story in his own words.”

But what can be generally believed about Da Ponte’s experience is his journey to America, and The Phoenix is at heart an immigrant’s story. “He spends so much of his life enamored of his new country, “O’Regan said. “But [he is] unable to take his eye off the old one, [from] which he is desperately trying to import everything, whether it’s literature, or olive oil, or salami, or opera.”

Though The Phoenix is not scrupulous historically, O’Regan captures the various times and places that feature in Da Ponte’s life through a wide mix of musical styles. “Tarik has given the piece a sort of feeling of pixilated memory,” conductor Patrick Summers explained. “He manages to invoke every era and every place—Venice and Vienna and certainly America—in ways that have nothing to do with pastiche.”

Hampson is particularly drawn to O’Regan’s music for the opera, noting that a passage called the Passacaglia is “going to blow people away.” Other sections, such as the Act II duet between the younger and older Da Ponte, recalls “the glories of Amadé Mozart,” he says.

“[Tarik’s music] is wonderfully atmospheric, and therefore ingeniously rhythmic, which makes memorization pretty challenging at times,” Hampson added. “It’s certainly not a walk in the park.”

Known primarily for his choral music, O’Regan writes in a style that combines tricky cross-rhythms with sweeping lyrical lines. Many scenes in The Phoenix involve the chorus as much as soloists. He also makes effective use of the orchestration, especially in his underscoring of the backstage scenes with harps, vibraphone, and high strings, elements that normally convey a sense of mystery.

But for an opera organized in traditional recitative-aria format, O’Regan seeks to recapture humor as an important device.

“Think about a new work in the opera house—what’s been missing is laughter from the audience,” the composer said. “And when you think about laughter and opera, it’s often eighteenth-century work or earlier,” the very world of Da Ponte’s own writing.

Aside from its humor, however, The Phoenix is a story about the power of art to transcend even the most scandalous of lives.

Art, theater, and poetry are ultimately Da Ponte’s legacy, Hampson said. “We all come and go, but what we leave behind is what’s important.”

The Phoenix premieres 7:30 p.m. Friday at the Houston Grand Opera and runs through May 10. houstongrandopera.org