Graf closes Texas Music Festival with a compelling Shostakovich portrait

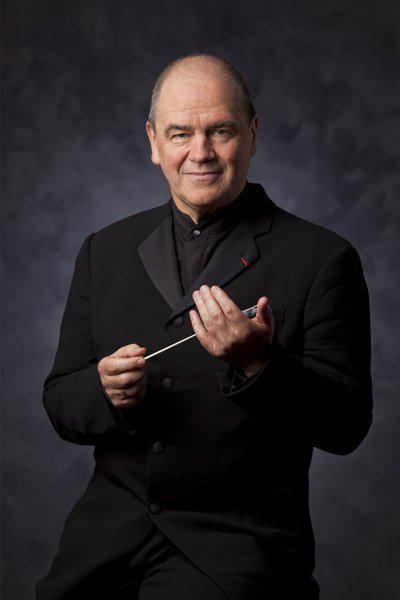

Hans Graf conducted the closing concert of the Texas Music Festival Saturday night.

Dmitri Shostakovich may be a familiar presence in the concert hall, but the Texas Music Festival painted a portrait of him Saturday that offered a compelling revelation.

For the Texas Festival Orchestra’s closing program, Hans Graf–Houston Symphony music director from 2001 to 2013–crafted a program that spanned Shostakovich’s entire career as an orchestral composer.

Speaking from the stage of the University of Houston’s Moores Opera House, the Austrian conductor said the works would show how a composer’s personal experiences and the world around him shape his work. The results fully lived up to Graf’s promise.

The little-known Scherzo in F-sharp minor showcased Shostakovich as an ultra-precocious 13-year-old, writing confidently for a large Late Romantic orchestra.

The brief Scherzo gave no hint that its creator would someday make distinctive symphonic statements, but that tied in with Graf’s point. Despite the minor key, the music was far from melancholy. With its crisp, muscular main section and sleekly melodious trio, it could have been the work of Alexander Glazunov.

Graf and the orchestra brought the Scherzo precision, vigor and heft, plus a generous dose of smooth string playing for the middle section’s tune, though the most exuberant moments proved overwhelming in the compact Moores Hall.

The familiar Symphony No. 1 came from a brash teenager ready to take the music world by storm–which is exactly what the symphony did.

The preceding Scherzo didn’t even hint at the wryness that would be one of the most distinctive features of the First Symphony. So the symphony’s smart-aleck bite, haunting lyricism and unbridled energy were all the more arresting Saturday due to the contrast with his juvenilia.

The orchestra didn’t quite command the razor sharpness to give the speediest parts their rapid-fire impact. But Graf and the group treated the symphony to huge vitality and eloquence.

The winds’ impish energy–particularly that of clarinetist Justin Best and bassoonist Erik Malmer–set the satiric tone for the symphony’s first two movements, and the full orchestra’s heft took over from there. The flutes’ warmth helped the second movement’s lyrical interlude offer a more personal note.

As the third movement opened, oboist Andrew Glenn’s slender, well-turned playing lent the main theme the voice-in-the-wilderness quality that recurs prominently in Shostakovich’s symphonies to come. And as the third and fourth movements unfolded, Graf and company gave them a vividness and intensity that also pointed toward later Shostakovich.

Amid Shostakovich’s brooding, the strings sometimes drew back to a hush, sometimes lashed out fiercely. And as the finale’s blazing conclusion approached, the orchestra’s punch and power lent the music ferocity despite the major-chord ending.

After intermission came the austere but powerful Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonnaroti, created the year before Shostakovich’s death. In 11 songs for solo singer and orchestra, the ailing composer used the Renaissance icon’s words to reflect on his life as an artist who struggled for decades against the Soviet regime.

Graf, the orchestra and Russian bass Nikolay Didenko–an alumnus of the Houston Grand Opera Studio training program–plumbed the expressive soul of each poem.

In “Creativity,” the orchestra’s clangorous fortissimo chords evoke the chisel-cleaving stone in Michelangelo’s poem. But when Michelangelo’s words ruminate on such topics as artists bedeviled by opposition or lies overtaking truth, Shostakovich turns more toward quieter, darker tones. The sepulchral hues of cellos and double basses often dominate the sound-picture. And while the vocal part occasionally cries out, it more often takes meditative, free-flowing path.

Didenko sang with a fluency and mellowness that sometimes let the songs sound conversational–which made their messages all the more arresting when his voice finally welled up.

In the first of three songs about love, “Morning”–about a sweetheart’s diaphanous dress–Didenko’s voice was as airy as the fabric he described. But his voice also could take on a somber gravity, even when it was quiet. And when it swelled, its fullness and vibrancy let the songs exude emotion and even anger without resorting to crudeness.

The orchestra’s shadowy, sometimes shimmering tones complemented Didenko’s subtle strokes. And its fullness and impact enhanced the intensity of his singing.

In the delicate final song, “Immortality”–a paean to the artist’s power to live through those who remember him–the woodwinds’ brightness harkened back to the wryness of the First Symphony.

The only blot on the performance came between movements. Posted in a balcony near the proscenium, Buck Ross, director of the University of Houston’s Moores Opera Center, unnecessarily recited each of Michelangelo’s poems in the original Italian–illuminating little for an English-speaking audience. With Ross’s piercing voice landing harshly on the ear, the superfluous narration made Didenko’s singing sound all the more subtle and expressive by comparison.

Posted Jul 05, 2018 at 3:31 pm by John

Perceptive and engagingly-written review of a tremendous concert. What a tragedy that Houston-at-large doesn’t get to read this discerning and thoroughly knowledgeable critic in its hometown newspaper. Only things I might add to what Steven Brown write: the last song of the cycle is based on a little “toy tune”, mostly in the piccolo, representing a kind of childhood innocence. After the despair of most of the cycle, this can bring tears to your eyes. Also, Buck Ross may have been reading “Italian”, but he’s decidedly NOT Italian, didn’t sound Italian, and the narration was a near-fatal miscalculation. Truly terrible.