Mercury brings Classical clarity to two Romantic symphonies

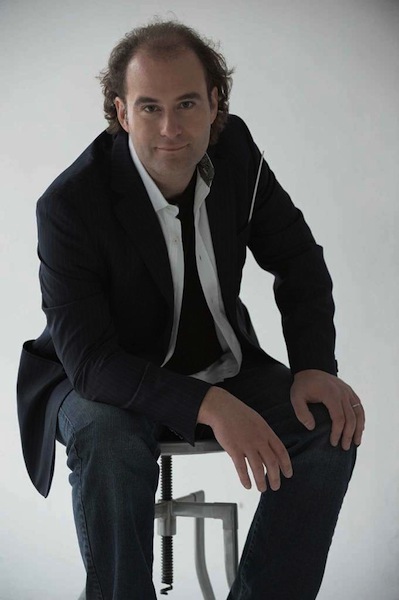

Antoine Plante conducted Mercury in music of Brahms and Mendelssohn Saturday night at Stude Concert Hall in Houston.

Here’s how far Houston’s Mercury period-instrument orchestra has evolved since its beginnings as a Baroque group: when it opened its main concert series for the season Saturday night, Mercury sidestepped the 17th and 18th centuries and planted itself squarely in the 19th.

Felix Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony commemorated the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s Protestant revolution. Mercury added a second historical angle by performing the symphony’s original version rather than the more-familiar revision. On the second half Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 2 continued the Brahms cycle Mercury launched last fall–following up on the survey of Beethoven symphonies the group completed in early 2016.

Like the Houston Symphony last month, Mercury performed in Rice University’s Stude Concert Hall as a Hurricane Harvey refugee. The storm knocked out Mercury’s usual home, the smaller of Wortham Theater Center’s two halls, for the entire season. Rice’s Shepherd School of Music took in the group for this and later programs.

Though it has roughly the same seating capacity as the Wortham hall, Rice’s Stude Hall is a bit more flattering acoustically–not surprisingly, perhaps, since this is a shoebox-shaped concert hall rather than a multipurpose proscenium theater. So the new venue made a congenial setting for Mercury’s foray into the Romantic period.

Mendelssohn, a Lutheran convert, paid homage to the Reformation by building his Symphony No. 5 around two iconic samples of Lutheran music: the so-called Dresden amen, which twice interrupts agitation in the first movement, and the hymn A Mighty Fortress Is Our God, which opens the finale. Dissatisfied with symphony’s first version, Mendelssohn revised it. But he ultimately refrained from publishing either score.

The revised version eventually came to light, and joined the Mendelssohn canon. But Mercury’s artistic director, Antoine Plante, went back to the original–which Germany’s Gewandhaus Orchestra played in Houston during a 2014 tour–for Saturday’s concert.

The most dramatic difference from the better-known version comes at the end of the slow movement. The flute launches a cadenza that draws in the rest of the winds, and they join voices in a surge of fervor worthy of a choir. Pizzicato strings punctuate the outpouring. The flute steps to the fore again to introduce A Mighty Fortress, and the finale takes off.

Perhaps Mendelssohn shouldn’t have second-guessed himself; Mercury made a persuasive case for this version. Principal flutist David Ross and the rest of the winds played the long-neglected passage with a fullness that made it a stirring setup for A Mighty Fortress. Led by Plante, the Mercury players brought the symphony vigor, clarity and airiness. Maybe a dash of ferocity in the first movement’s climaxes would have made the strings’ ethereal Dresden amens more powerful. But the orchestra’s incisiveness–especially from the strings–ensured that that music’s fire came through.

The second movement moved with a dance-like spring in its step, and the Andante sang out with yearning and sweetness. After those full-throated winds heralded the final celebration, the rest of the orchestra sprung into action, propelling the symphony to a vital, ringing close.

Created almost immediately after his Symphony No. 1, Brahms’ Second Symphony and its prevailing optimism complemented its predecessor’s storminess.

Plante and Mercury brought out the music’s lyricism and gleam. In the first movement, Plante let the melodies flow, letting the shapeliness of their contours and the subtlety of their colors tell the story as the music moved between sun to shade. The orchestra was occasionally a little fuzzy during the rhythmic gearshifts that help animate Brahms’ music. But the lines always came back into focus.

The cellos spun out the Adagio’s opening theme gracefully, and the entire movement unfolded with much the same natural flow. Thanks to the lucid balancing, details that may get lost during modern-instrument performances were able to shine through–for example, euphonious byplay between the cellos and winds as they accompanied the violins.

Elegance and dash alternated in the third movement. The woodwinds’ assurance belied the treacherousness of period wind instruments–though occasional cracked notes elsewhere in the symphony were a reminder. And the orchestra balanced breeziness and brilliance as it swept through the finale. Mercury’s years devoted to 17th- and 18-century music evidently laid a secure foundation for its current burgeoning Romanticism.