Compelling characters, static music as HGO premiere fetes Rothko Chapel

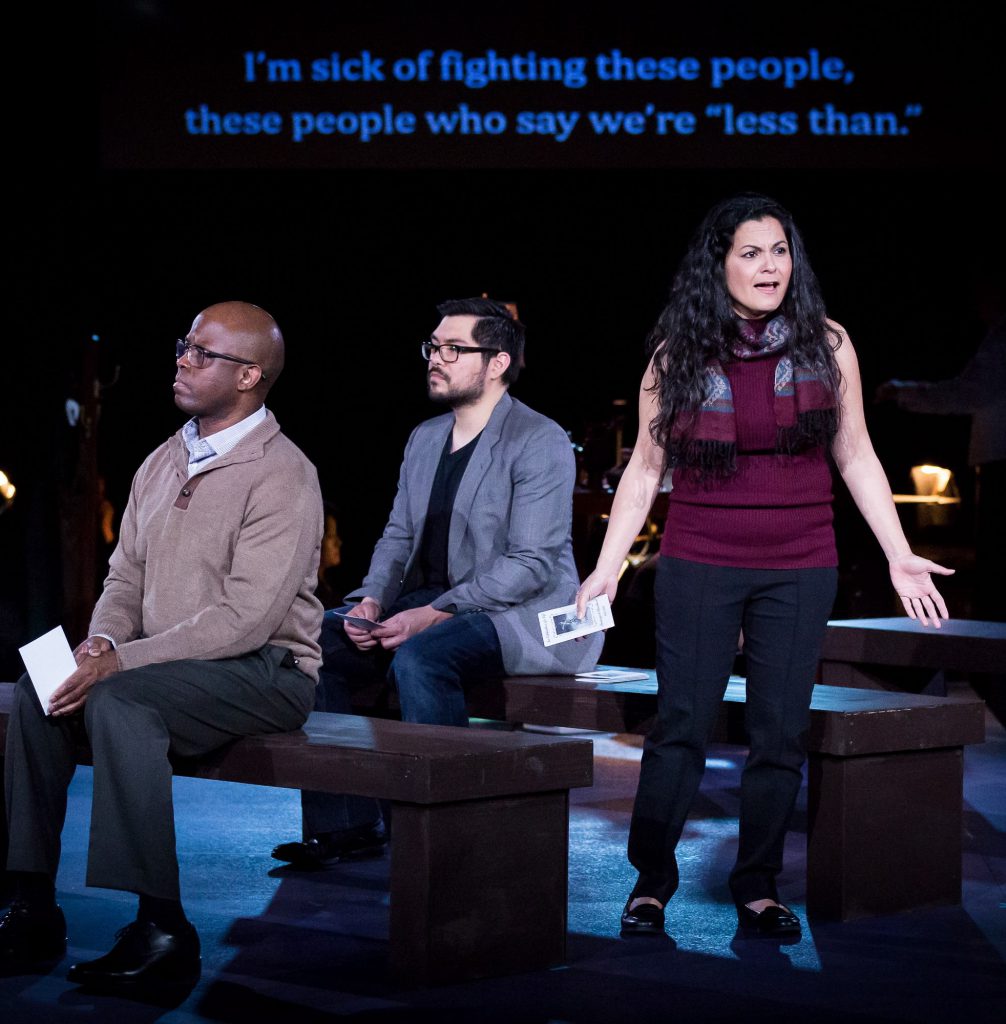

Rodney White, Alexander P. Garza, and Cecilia Duarte in the world premiere of Laura Kaminsky’s “Some Light Emerges” at Houston Grand Opera. Photo: Lynn Lane

Fourteen massive Mark Rothko canvases, all-black but varied in tint and texture, lead visitors to the Rothko Chapel away from life’s pressures and into their own reveries. Composers, just like anyone else, feel the effect of the austere Houston landmark.

Morton Feldman, commissioned by its founders, composed his ethereal choral piece Rothko Chapel in 1971, the year of its opening. Kaija Saariaho likewise evoked the urban sanctuary’s aura in her chamber work Sombre.

Now the chapel is the unseen but ever-present driving force of a new opera: Some Light Emerges, by composer Laura Kaminsky and librettists Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed.

In the 75-minute chamber opera, premiered by Houston Grand Opera this week, the chapel exerts its quiet power on five visitors, from a construction worker escaping the Texas heat to a teenager intrigued by art and a woman lingering after a friend’s memorial service. Kaminsky and company interweave their fictional stories with the real-life one of the chapel itself. We see that architectural saga, as portrayed by Dominique de Menil, the Houston art collector and philanthropist who envisioned the chapel in 1964 and spearheaded its creation.

Those are the opera’s six characters and, in the second and final performance Friday night, Some Light Emerges tells their stories with directness and simplicity. (A grand operatic scale would hardly suit a construction worker or teenaged Hurricane Katrina refugee, after all.) The seven-player instrumental group fires off a few outbursts when Menil referees a telephone battle between Rothko and her equally strong-willed architect, Philip Johnson.

But Some Light Emerges’ music is mainly transparent, conversational and meditative. Kaminsky has a knack for making characters

sound real even while singing operatic lines. Construction worker Tom, entering a building he knows nothing about, sizes it up with a builder’s matter-of-factness. When we meet Margie, a wife and mother with nothing to do in the afternoon, she’s chirping about a spur-of-the-moment lunch at a French restaurant.

Cece, the teenager, exudes give-me-a-break disdain as she describes her American history class.

Menil plans a reception for the city council with a veteran hostess’ craftiness about handling guests. Alecia, the woman at the memorial, laments the hard-heartedness of her late friend Beauregard’s family and church, who turned their back on him because he had AIDS.

Albert, an Algerian immigrant bedeviled by post-9/11 hostility toward Muslims–a religion he doesn’t even belong to–has the most powerful scene. As he laments his treatment, his voice wells up in plaintive melismas that hark back to Moorish music.

Except for Albert’s outcry, though, the characters almost never take flight in melody or fervor. Plain speaking, or plain singing, predominates, and it comes at a musical cost. Rothko’s art at some point captivates and quiets each of the characters, so the opera regularly returns to essentially the same mood. Some Light Emerges becomes static: a string of episodes, each delivering its message, but lacking overall musical development ad dramatic momentum.

The cast’s conviction and flair helped animate the opera Friday. Soprano Yelena Dyachek gave Menil dignity, slyness and resolve. Christian Pursell’s hale-and-hearty baritone helped construction worker Tom come across as a regular guy. Soprano Amy Petrongelli made an adroit shift from perkiness to gravity as Margie.

Mezzo-soprano Cecilia Duarte revealed shadings of both humor and indignation as Alicia remembered the departed Beauregard and his hardships. Tenor Karim Sulayman built Albert’s laments to the point of desperation. And mezzo-soprano Zoie Reams brought the teen Cece a combination of youthfulness and courage.

Director Robin Guarino’s fluent staging helped all those human traits come across. The action unfolded on a simple platform in the Ballroom at Bayou Place, an entertainment complex in downtown Houston. HGO’s production didn’t try to duplicate the iconic chapel’s appearance — though it did incorporate some actual benches contributed from the chapel. An octagonal lighting unit above the stage evoked the chapel’s shape.

Otherwise, it was up to conductor Bradley Moore and the ensemble to set the scene. Whether it was evoking fog enclosing an airport, mimicking Texas crickets or underlining the characters’ ruminations, the group played lucidly. And thanks to Kaminsky, the somber tones of the bassoon and trombone sometimes hinted at Rothko’s solemnity.