Graf, Ohlsson explore Rachmaninoff rarities with DSO

Garrick Ohlsson performed Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 4 with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra Friday night.

An all-Rachmaninoff program might reasonably be expected to include one of the familiar warhorses of Rachmaninoff’s oeuvre—the Second Piano Concerto, Second Symphony, or the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. But none of those familiar pieces are on display this weekend at the Meyerson Symphony Center.

Instead, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and guest conductor Hans Graf are sharing two of Rachmaninoff’s lesser-known works with audiences: the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Minor, with soloist Garrick Ohlsson, and the Symphony No. 1 in D Minor.

Both of these works share the regrettable distinction of being received poorly and thus sending Rachmaninoff into depressions at the opposite ends of his career: Rachmaninoff completed his First Symphony when he was 22, and premiered the third and final version of his last piano concerto when he was 68. While neither piece features the indelible melodies of his better known works, Friday’s DSO concert made a compelling case that both of these works deserve more frequent performances.

It’s an oft-cited story that Rachmaninoff was at the premiere of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in 1924. His admiration for Gershwin, and for American jazz more generally, heavily influenced his fourth and final piano concerto. The middle movement of the concerto is a blues-tinged bit of loveliness that is the closest listeners get to familiar Rachmaninoff lyricism.

Ohlsson is perhaps best known for his Chopin, but the American pianist is an equally fine interpreter of late Romantic repertoire, as well. He has a dazzling range of tonal colors and a masterful musicality. He tended to play within the orchestra rather than out in front of it, letting the music be the focus, rather than his own playing.

Sensitive, compelling phrasing was amply on display in the central movement, as Ohlsson wove a sinuous line of melody, and the orchestra followed suit. The dark but technically complex outer movements allowed both the orchestra and Ohlsson to show their virtuosity.

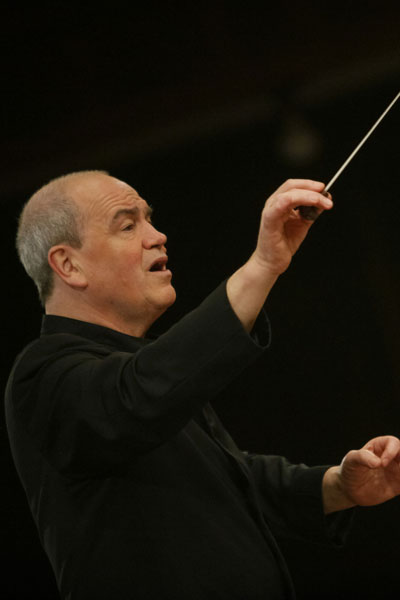

Hans Graf

The orchestra responded in kind. Sometimes the Dallas Symphony’s precision suffers under guest conductors, who may not prepare the orchestra as meticulously as music director Jaap van Zweden.

Yet Friday night they were on point under Graf, who is former music director of the Houston Symphony and is a regular visitor to the DSO’s podium. Brass, especially, played with impeccable ensemble and glowing tone. The orchestra as a whole supported Ohlsson skillfully; while he certainly has a huge dynamic range available to him, Ohlsson never overplayed, and the orchestra, too, held back as needed, rarely overbalancing the soloist.

Despite Rachmaninoff’s youth when he composed his Symphony No. 1, it is not a student piece. By the time he wrote his first published symphony, he had written a student symphony, most of which has been lost, and his first piano concerto. Still, his own distinctive voice had not yet developed. Worse for a young composer, the first performance was a catastrophe. Rachmaninoff believed that the conductor, Alexander Glazunov, was drunk on the podium, and he left in distress before the piece was over. The reviews were eviscerating.

The tone of the Symphony No. 1 is dominantly gloomy, even more so than in his later works. It uses a triplet motive in each movement, creating what early critics saw as repetitiveness, but a more sympathetic ear might hear as thematic integration. Within these motives, though, Rachmaninoff seems to be trying to find his way. He uses the Dies Irae in the first movement, and takes on a bit of a martial tone in spots, with a fourth movement fanfare in the brass, accompanied by drum and cymbal blasts, that seems like a portent of war. Also in the fourth and final movement, a grand pause creates a false ending culminating in a single gong hit before the real coda.

While the orchestra’s playing of Rachmaninoff’s symphony was a bit less clean than the concerto, the performance was still exemplary under Graf’s unshowy but assured baton. Principal oboe Erin Hannigan showed a striking timbral range in her solos: bright in the first movement, then matching the subdued tone of the muted strings in the third. A fugal section in the first movement is begun by the second violins, whose ensemble and tone were flawless.

This program will be repeated 2:30 p.m. Sunday. mydso.com