In Dallas Opera’s return voyage, “Moby-Dick” remains a compelling stunner

Jay Hunter Morris as Captain Ahab in Jake Heggie’s “Moby-Dick” at Dallas Opera. Photo Karen Almond

Composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer debuted their Moby-Dick at Dallas Opera in April, 2010. At the conclusion of that premiere, the crowd roared its approval of this bold new opera. That production of Moby-Dick is being revived by the same company, which opened Friday night.

A frequent complaint about the novel Moby-Dick is that too little of the book is about the search for the whale, and too much of it is abstract philosophy: witness the famed chapter on “The Whiteness of the Whale,” which is beautiful but abstruse, and doesn’t seem to further the plot in the least.

For those who raise such objections, Heggie and Scheer’s opera will come as welcome relief. They dismiss with most, but not quite all, of the philosophy, retaining Melville’s characters and plot outline. They even dismiss with the novel’s first person, retrospective narrative voice, saving its iconic opening line, “Call me Ishmael,” for a goosebump-inducing ending, spoken by Greenhorn to confirm what we’ve suspected all along. In the final scene, Greenhorn finds himself washed up on a beach after the deaths of all of his shipmates and the destruction of the Pequod in Ahab’s bootless struggle to kill the white whale. It’s as if Ishmael will only now begin telling the story we have just seen.

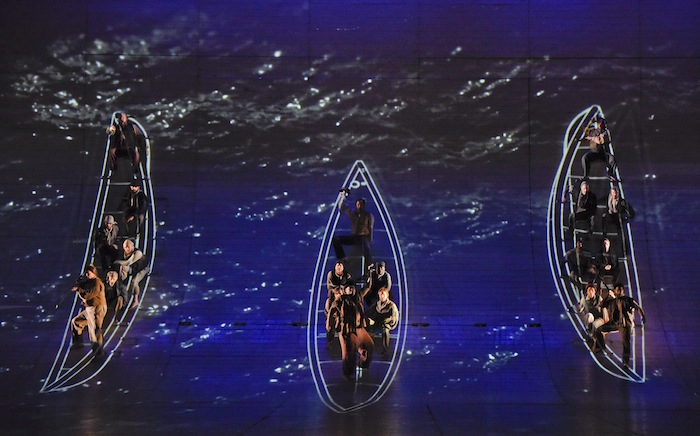

Robert Brill’s sets and Elaine J. McCarthy’s projections are still some of the most astonishing and gorgeous to grace an operatic stage. There are clear logistical difficulties associated with creating an opera out of a novel such as Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby-Dick, because the novel is set entirely aboard ship or on precarious harpoon boats, yet Brill and McCarthy solve these difficulties brilliantly.

The opera opens with a field of stars gradually emerging from darkness, then being crisscrossed with sextant lines. These lines become the outline of Ahab’s ship, the Pequod. It’s hard to imagine a more breathtaking opening visual. The rear of the stage features a slanted quasi-climbing wall—the call for supernumeraries asked for people who were “athletic, agile, adventurous, and unafraid of heights,” with good reason. The chorus and the supers climb the wall periodically, as a stand-in for some of the Pequod’s rigging.

Photo: Karen Almond

In the first whale hunt, though, the magic happens: projections of harpoon boats and ocean waves superimpose on the people perched on the wall, to create a persuasive and stunning image of men on the open ocean, seeking leviathans in veritable rowboats. When the men are tossed from the boats, they tumble and roll down the slanted rear wall, a near-perfect effect.

An almost all-male cast can create a host of problems, both musical and visual. Costumes by Jane Greenwood, though appropriately muted, were distinctive enough to make differentiating among characters easy. (The exception to the low male voices was the boy Pip, played as a trousers role by soprano Jacqueline Echols.) Heggie’s music thoughtfully characterizes each role, creating effective individuation. Choruses occasionally sound more like operetta, though surely deliberately so/

Tenor Stephen Costello is brilliantly reprising his role of Greenhorn (and just wrapped the role of Lensky in Dallas Opera’s final Eugene Onegin performance Saturday). His voice is powerful yet youthful-sounding, and brings needed poignancy to the role. First Mate Starbuck, likewise, is again sung by baritone Morgan Smith, who offers convincing muscularity and authority

But Ahab, who was sung in the premiere by a commanding Ben Heppner, is in this production sung by tenor Jay Hunter Morris. The role of Ahab is a challenging one, and while Morris has the stamina for the role, he lost the pitch center fitfully Friday evening, and incorporated quirky diction that sometimes distracted. Also Ahab should be simultaneously terrifying and vulnerable, powerful and, as he sings, “madness maddened!” Morris’s portrayal was often too gentle and inward to be convincing.

Musa Ngqungwana excelled as Queequeg. South African’s bass-baritone is resonant, assured, and soothing as he develops a warm friendship with Greenhorn. Indeed, in place of the love duet in a more conventional operatic plot, there is a duet between Greenhorn and Queequeg, sung from the riggings, a beautiful paean to bromance.

This opera features some of the most challenging singing conditions in recent memory. Ahab, of course, sings his entire part balanced on a faux artificial leg. Jacqueline Echols sings her big aria suspended above the stage, as she swims from stage left to stage right, having been tossed from the harpoon boat. Pip goes mad as a result of his near-drowning; Ophelia-like, he “too much of water hast,” and spends the rest of the opera shaking his tambourine and talking in semi-prophetic nonsense. Echols, who has an unusually warm, full soprano, portrays Pip’s unraveling with an appropriate combination of pathos and bewilderment.

The Dallas Opera orchestra under the baton of Emmanuel Villaume sounded better than it has in recent outings, even given the difficulty of this music: they were precise, crisp, and effectively balanced with the singers.

While this revival of Moby-Dick may not be as thrilling and lacking the sense of fresh discovery as the premiere six years ago, it is still a masterpiece of singing, writing, and stagecraft, and is worth a first—or second—viewing.

Moby Dick runs through Nov. 20. dallasopera.org; 214-443-1000.